Rhetoric and Reality: An analysis of government’s performance (Sep 2023 – Aug 2024)

Download the full report: https://doi.org/10.59186/SI.5F6F649N

Read the report summary: 2024 Zimbabwe Government Assessment Summary

Table of Contents

| 1.0 Introduction |

| 2.0 Background |

| 3.0 Dimensions of the Crises |

| 4.0 Methodology |

| 5.0 Findings |

| ___Economy |

| ___Governance |

| ___Social Services |

| ___Rural Development |

| 6.0 Conclusion |

1.0 Introduction

Zimbabwe has since the turn of the century been characterised by a multifaceted and interlocking crisis ranging from the political arena to the economic and social sectors. At its peak, the crisis was associated with rising unemployment, rapid emigration into neighbouring countries and overseas destinations, shortage of basic consumer goods, collapse of the local currency and steep decline in the quality of social service delivery. Drivers of the crisis at the time included the collapse associated with structural adjustment, the fast-track manner in which the land reform program was implemented in the early 2000s, failure on the part of the ruling party to rein in its errant elite class that was involved in many forms of corruption including hoarding large scale commercial farms and the general intolerance of dissent. It has been close to two decades since the crisis manifested. Today the majority of the indicators have either worsened or stabilised. It has become common or routine for graduates from tertiary institutions to remain unemployed or to be under-employed (working in a position that does not require the qualifications they attained). There is a resurgence of massive emigration. Social services, especially health, have in some ways worsened. For instance, there is an increasing number of Zimbabweans seeking treatment or just giving birth in neighbouring South Africa. The economy has gone through waves of hyperinflation and moments of respite due to the introduction of various currency fixes. Since the turn of the century, the country has gone through four (4) variations of the local currency.

The change of government that happened in 2017 and then the christening of the same government through the 2018 elections seemed to suggest a new and bold approach towards resolving the crisis. There have been a number of strategies, beginning with the Transitional Stabilisation Programme (TSP) of October 2018 and the National Development Strategy 1 2021 – 2025 (Veritas, 2018, 2021). These strategies alongside many other short and medium-term plans were/are meant to contribute towards Zimbabwe’s quest or desire to be a middle-income country by 2030. However, fortunes have not drastically changed for many. Employment opportunities have been very scarce. In fact, the majority of the labour is now employed in the informal sector. There has been some recovery of local production of a wide range of manufactured goods and in the process reducing the import burden. However, it does not seem to have made a huge impact on employment creation. The quality of public education and health services has not improved. There is still a large number of Zimbabweans without affordable access to decent healthcare and education. Partisan-based political polarisation has worsened under the current regime. There is not only intolerance of different points of view but an ongoing effort to silence dissent. The largest opposition party has for all signs and purposes collapsed.

Since 2017, we (www.sivioinstitute.org) have been tracking the performance of the government here at www.zimcitizenswatch.org and we have written a number of reports based on results produced by the tracking platform (Murisa, et al, 2023). The progress has been uneven. The government has made some decent (but not enough) progress in certain sectors such as agriculture and performed dismally in the areas of employment creation, social service delivery and governance reforms, such as the battle against corruption. Does the above suggest that we as Zimbabweans are incapable of resolving the crisis? Admittedly it will take more than the central government to help fix the country. There is a need for a broadly shared vision and consensus on the national project of inclusive recovery, a more engaged and reform-oriented local government and an innovative and highly productive private sector. However, all three (3) mentioned above require leadership from the government to enhance the broadening of participation in the national development project, building trust and confidence in the market. The question, maybe, should shift to ‘has the government done enough to ensure a multi-stakeholder-driven national development process?’ The report focuses on government performance, given its primary role in fostering an ecosystem of inclusive national development. The objective of the report is to contribute to and nurture more evidence-driven discussions on the progress made towards resolving the interlocking crises.

2.0 Background Operating Environment

It is also important to note that a discussion such as this one has to take into consideration externalities that affect government performance. The period under review cannot be analysed in isolation from the preceding two decades of independence. By 1991 the government had embarked on structural adjustment to (i) reduce government expenditure and involvement in the economy and (ii) to liberalise the economy. Between 1991 and 1997 economic growth fell. Unemployment almost doubled. From having a trade surplus in the 1980s, a trade deficit was created. The Human Development Index (HDI) dropped from 0.571 in 1995 to 0.491 in 2002. By 2004 the World Bank acknowledged that liberalisation “largely failed. Social progress slowed, per capita incomes declined, and poverty increased” (Debt Justice, 2024).

During the period under review, the government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) has had to respond to the effects of natural disasters especially the effects of cyclone Idai, two years of COVID-19 and the ongoing El Niño induced drought. Furthermore, for the most part, the GoZ has been operating under a variety of austere economic instruments that limit it from accessing international financing. There is a debate on whether to call these ‘sanctions’ or ‘measures that arise from non-compliance with debt conditions’. The reality is that the GoZ has been under a ‘pariah status’ like position with many Western institutions for a number of reasons, including the manner in which it carried out compulsory land reform and its precarious debt situation with many lenders. Indeed, in many instances, government and ruling party actors have identified the ‘sanctions’ against the country as one of the major reasons behind the failure to resolve the economic dimensions of the crisis. There has been some shift in the United States government’s policy against Zimbabwe. On March 4, 2024, President Biden terminated the Zimbabwe Sanctions Program, unblocking all individuals, entities and property that had been blocked under that authority. However, the termination was about refocusing from targeting the ‘people of Zimbabwe’ towards specific individuals through the Global Magnitsky Sanctions. A total of 11 individuals and three (3) entities had been blocked under the now-repealed Zimbabwe program. However, the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZDERA) remains in place.

Related to the above is perhaps one of the most contentious government initiatives – the compensation of former large-scale commercial farmers (mostly white) who lost their farms during the fast-track land reform program. The GoZ made a commitment of US$3.5 billion as part of the compensation agreement, billions that the heavily indebted country decidedly does not have. To date, there has been very little that has actually been paid out in terms of compensation.

3.0 Dimensions of the Crises in Zimbabwe

The causes of the crises are beyond the focus of this report but there are many helpful debates on this (see for instance Murisa and Chikweche 2015; Helliker and Murisa 2020). The Table below provides a detailed description of the various dimensions of the crisis since the turn of the century. There has been an uneven improvement or worsening in some of the dimensions of the crisis.

| Crisis in Zimbabwe | |

| Dimension | Characteristics of the Crisis |

| Economic | High levels of unemployment |

| Hyperinflation | |

| International isolation (sanctions) | |

| Acute shortage of foreign currency | |

| Weak or no economic growth as measured by GDP | |

| De-industrialisation / Closure of companies | |

| Limited utilisation of factory capacity | |

| Collapse of infrastructure | |

| High prices of goods | |

| Cash shortages | |

| Weak demand for goods | |

| Agriculture | Contestations over land reform and disagreement over the compensation model |

| Land reform induced decline/collapse of agricultural performance (2000 – 2008) | |

| Food crisis/increase in a number of food-insecure households | |

| Shrinking of land under irrigation | |

| Shortage of productive inputs | |

| Climate change-induced challenges | |

| Health | Shortage or unavailability of essential drugs |

| Shortage of machines to carry out basic procedures | |

| Skill migration (Doctors and Nurses) | |

| Poor remuneration for Doctors and Nurses | |

| New global pandemic | |

| Education | Growth in population not matched by the increase in education infrastructure |

| High levels of teacher absenteeism | |

| Skills migration of highly qualified professionals | |

| Poor remuneration of teachers | |

| Shortage of textbooks | |

| Increasing number of school dropouts | |

| Housing | Weak or no supply of low-priced housing stock |

| Increasing number of families on housing waiting lists | |

| Weak financing mechanisms to support the supply of housing especially for “Bottom of the Pyramid” based households | |

| Increasing prices of stands | |

| Increasing number of people living in informal settlements | |

| Political and Governance | Polarisation |

| High levels of intolerance of dissenting views | |

| Weak or no respect for the rule of law | |

| Failure to manage succession within political parties | |

| Abuse of electoral processes | |

| Election-based / related violence | |

| Increase in the number of citizen-based protests on government actions | |

| Corruption | Abuse of office and state funds through collusions to over-price materials, goods and services supplied to the government |

| Deliberate actions/collusions to deprive the government of its revenue such as trade mispricing, under-invoicing, smuggling | |

| Deliberate weakening of procurement procedures to benefit otherwise incompetent bids | |

| Poverty | Increasing number of urban and rural households without an adequate source of food |

| Number of those living under the poverty datum line | |

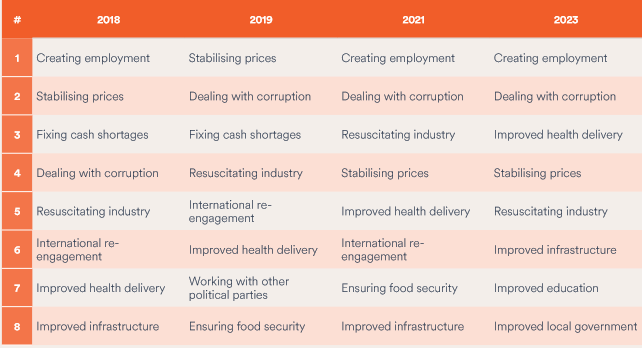

The discussions of the crisis are not limited to elite or academic abstractions but are part of everyday lived realities or trauma amongst many in Zimbabwe. Findings from the Citizens’ Perceptions and Expectations (CPE) surveys carried out annually provide us with insights on what Zimbabweans expect their government to focus on. Repeatedly, for five years, respondents (nationally representative sample) have urged the government to focus on; (i) employment creation, (ii) ensuring affordable prices, (iii) improving health delivery and (iv) addressing corruption (Jowah, 2023). These concerns have featured at the top of the list since we started the CPE surveys. Furthermore, when we ask respondents to rank factors that possibly constrain government effectiveness, they always identify corruption followed by limited capacities within both the national and local governments.

There are other emerging dimensions of the crisis that are not featured in Table 1 above, such as the challenge of drug abuse amongst the youth. We consider these not to be part of the original set of dimensions but this increase in drug abuse amongst the youths, among others, suggests a possibility of the emergence of new dimensions of the crisis in the absence of effective responses. The lockdowns associated with COVID-19, for instance, helped to surface the level of inequality and the collapse of the social welfare system. The discussion that follows examines the progress made to address these dimensions of the crisis since 2017.

4.0 Methodology of Tracking and Weighting Government Performance Since 2017

In the first five (5) years, we organised the policy conversion tracker on the basis of the promises made in the ZANU-PF patriots (2018) manifesto entitled “Unite, Fight Corruption, Develop, Re-Engage, Create Jobs”. The manifesto outlined 234 promises which we clustered into nine (9) sectors (Economy, Agriculture & Rural Development, Social Services, Trade & International Relations, Local Governance, Youth & Gender, Governance, Politics & Civil Rights and Corruption). During the five (5) years of tracking using this clustering, the government implemented 16 promises (7%) and managed to keep 189 promises (81%). Twenty-one promises (9%) were not started, and seven (7) promises (3%) were broken.

The ruling party did not produce a manifesto for the 2023 elections and instead campaigned based on previous performance. In the process reneging from what has become part of the tradition or best practice of elections – making a set of promises to the electorate. Our methodology remains consistent as it entails tracking the actions that the central government has undertaken since the elections and capturing them on the ZIMCITIZENSWATCH (ZCW) platform. The actions are gathered from various digital news sources, press briefings and other official government statements.

In the absence of a manifesto, we decided to track the ruling party on the basis of commitments made in the NDS1 (Veritas, 2021). We have grouped 228 promises captured in the NDS1 into 21 priority areas that fit within four (4) main clusters, namely Economy, Governance, Social Services and Rural Development. An overview of the state of progress made in these four (4) areas is noted below using a Red, Amber, and Green (RAG) analysis to determine the extent of the progress made. Red means that no progress or effort has been made towards converting a policy commitment into an action. This is still an area of concern. For sectors in Amber, it indicates that the efforts being implemented need to be enhanced and strengthened to truly address the concern. Green indicates the completion of a policy action from conception to delivery. There are most likely to be very few greens in analysing actions carried out over one year. We take cognisance of the fact that this government (second republic) has been in power since November 2017.

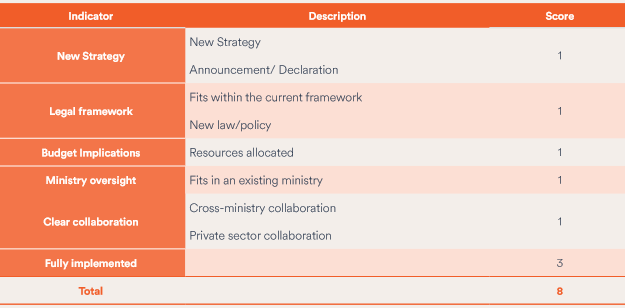

Our approach combines tracking and weighted scoring of the impact of each government intervention. Once the actions of the central government have been gathered and verified, we then produce an annual barometer score. The revised tracker assesses the quality of the action by giving it a weighted score out of eight (8) and is assessed across six (6) indicators outlined below:

The scores are then taken per action and are aggregated as an average across each priority area and each cluster to give a final score that is then assessed using an RAG analysis described below:

| Colour | Description | Score |

| Red | Red indicates that no progress or effort has been made towards addressing this sub-sector. This is still an area of concern. | 0-33% |

| Amber | Amber indicates that the efforts being implemented must be enhanced and strengthened to address the concern. | 34-66% |

| Green | Green indicates that the policy actions are working to address and mitigate the issues that citizens highlighted, and progress is heading in the right direction. | 67-100% |

5.0 Alignment of Government Actions to Crisis Framework/ Dimensions

5.1 Government Overall Performance by Cluster

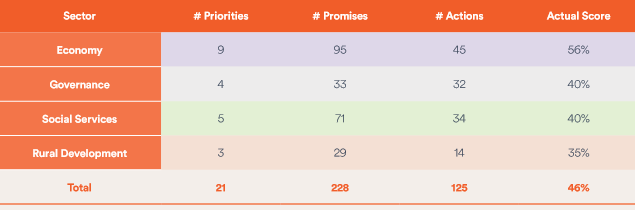

The following discussion evaluates government performance through the thematic clusters established in the tracking methodology (refer to Figure 1 above). As already indicated the performance of the government around 228 policy promises (commitments) made in the NDS1.

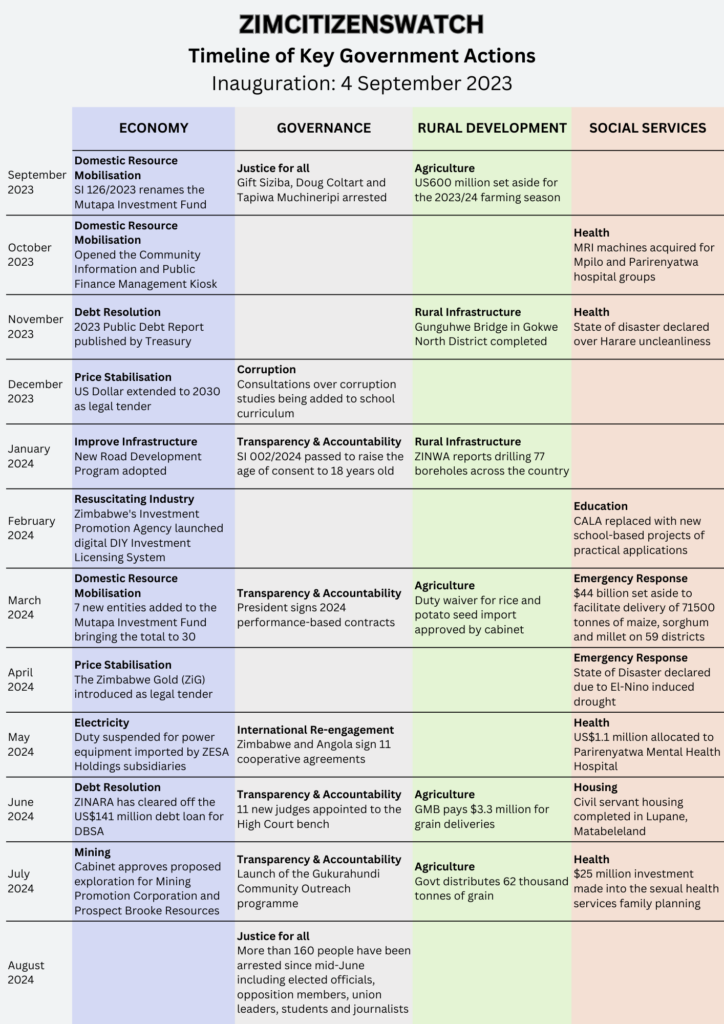

The timeline below provides an overview of some key actions that the government undertook from 4 September 2023 through to 31 August 2024. The actions range from the development of new policies to taking steps towards amending existing legislation, the operationalisation of the Mutapa Investment Fund; introducing measures to deal with the ongoing cholera epidemic and the new threats faced with the onset of the El Niño-induced drought which will have a huge impact on the 2023/2024 agricultural season; the introduction of the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency, the suspension of duty equipment imported by ZESA Holdings and the launch of the Gukurahundi community outreach programme.

5.1.1 Economy

The Zimbabwe economy has been a key talking point over the last few decades. The economy has shed a significant number of jobs and seen a number of companies collapsing or migrating to other jurisdictions since the turn of the century. However, there seems to be some form of a turnaround albeit not adequate. The country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown from a base of US$17.58 billion in 2017 to US$26.54 billion by the end of 2023 (World Bank, 2023). The country’s GDP has been growing at an average of 1.3% each year since 2017. There is an ongoing debate on growth levels; the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on the one hand expects the economy to grow by 3.2% in 2024 (IMF, 2024) whilst the government expects a growth of 3.5% (Veritas, 2024). According to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency ZimStat (2024), formal sector employment has grown from approximately 24.4% in 2019 to 28.6% in 2024 (Labour Statistics). In 2020 the government officially removed the requirement for local ownership as part of measures to attract foreign direct investment. The government introduced the Zimbabwe Investment Development Authority (ZIDA), meant to be a one-stop shop for all businesses intending to operate in the country (Vhumbunu, 2022).

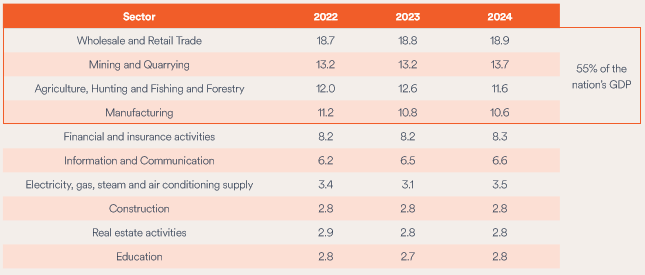

The economy largely relies on trade (wholesale and retail), agriculture and mining. Local manufacturing has grown by 8% since 2017. Industry capacity utilisation was 45.1% in 2017 and grew to 53.2% in 2023 (CZI, 2023). Table 6 below shows the contribution of each sector towards GDP. Manufacturing has slightly improved but is yet to reach its pre-ESAP highs of 25% towards GDP.

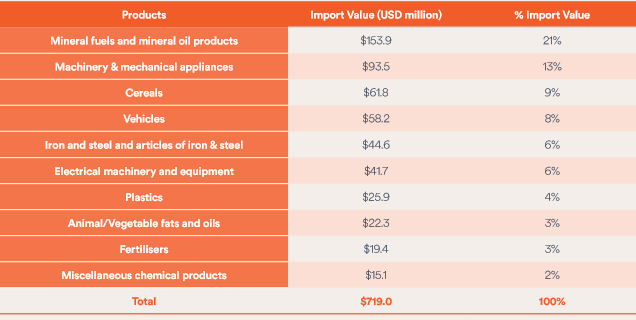

The dominance of the wholesale and retail sectors in the absence of significant growth in manufacturing suggests an overall dependence on imports. According to ZimStat (March, 2024) the country’s import bill stands at US$719 million and is evenly divided into productive and consumer goods. Areas of concern as per Table 7 below are the high levels of vehicles, (8%) cereal (9%), plastic products (4%) animal/vegetable fats and oils (3%) and fertiliser imports (3%). A comprehensive import substitution strategy will contribute towards savings on the scarce foreign currency.

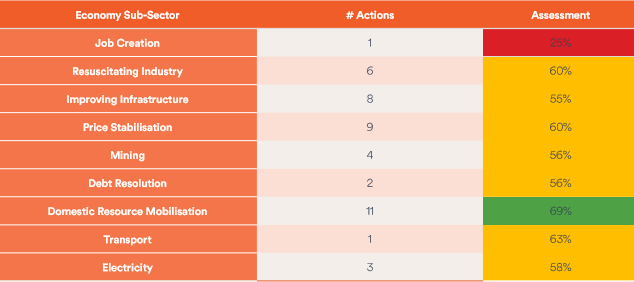

Commitments from the NDS 1 mostly focus on improving the economy. More than a third (42%) of the promises (95/228) captured on our tracker seek to improve the economy. To date, the government has carried out 45 actions in the economy sector since its inauguration in September 2023. Government actions were mostly focused on domestic resource mobilisation (11), and price stabilisation (9) followed by actions meant to improve infrastructure (8) and resuscitate industry (6). There have been limited government actions in terms of job creation and improving public transport.

The introduction of a new currency, the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) currency launched on the 5th of April 2024 was one of the most significant actions taken during the period under review. (Sibanda, 2024). According to the government, the introduction of the local currency is part of the measures to resolve the problem of unstable prices. The new currency replaced the rapidly depreciating Zimbabwean Dollar (ZWL) which had reached an official rate of over ZWL30,000.00 to US$1 at the start of April 2024, a depreciation of over 142% from the exchange rate in January 2024. The government put aside a total of US$575 million through a combination of gold and foreign currency reserves to bolder the structured currency (Mhlanga & Chikandiwa, 2024). This policy move sought to address the challenge of exchange rate volatility and help curtail inflation. The official rate of the ZiG to the US$ when it was launched was US$1 to ZiG13.56.

Actions focused on resuscitating the industry include ZIDA’s launch of the country’s first-ever digital Do-It-Yourself (DIY) investment licensing system (NewZimbabwe, 2024), aimed at facilitating investment in the country by easing the process of investors applying for and receiving their licenses. The portal is expected to cut down the process of applying for a license to between 2 – 5 days. In the 2024 National Budget, the Government has set aside an amount of ZWL220.8 billion as part of the strategy to support the local industry. Furthermore, the government launched the National ICT Policy, the Smart Zimbabwe 2030 Master Plan and the National Broadband Plan. These are meant to improve the performance of the economy by aligning with new ICT-based best practices.

The challenge of creating decent work is perhaps one of the most difficult tasks that the government has to contend with. The most recent skills audit was carried out in 2018. It was found that in terms of the labour market, Zimbabwe suffers from huge skills deficits (averaging 61.75%) with wider gaps in science-related areas and applied arts and humanities compared to business and commerce which is oversubscribed by 21% (Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education, 2018). Furthermore, ZimStat’s Labour Force Survey conducted in the fourth quarter of 2021 revealed that 86% of the employed population were informally employed. It is also important to note how unemployment affects the youth; Zimbabwe’s share of youth Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) increased from 35.2% in 2014 to 44.7% in 2019 for the youth aged between 15 to 24 years. A similar trend was noted for the youth aged between 15 to 35 years where their NEET increased from 27.4% to 47.1% over the same period (ZIMSTAT, 2019). It has continued to rise and in the first quarter of 2024, NEET for 15-24 years was 49.4% and for 15-35 it was 48.9% (ZIMSTAT, 2024). The government scored the lowest under job creation. One of the actions here has been the introduction of a new ministry in the Office of the President and Cabinet, namely the Skills Audit and Development Ministry whose key focus is on human capital development and skills alignment (Chidakwa, 2023). The ministry since February 2024 has been engaged in skills audit consultations outlining the mandate of the Ministry and engaging stakeholders around human resource and skills challenges. However, it is not yet clear how this new ministry, with its focus on human capital development, will ensure the optimal utilisation of existing skills in the country. This could be a case of misdiagnosis of the problem or prioritisation. The country has ten state universities and available data indicates that less than 25% of the graduates actually go on to secure formal employment.

The government scores highly on Domestic Resource Mobilisation. The revenue authority (ZIMRA) collected above its target in 2022 and 2023 the collections from corporates were ZWL$604 billion against a target of ZWL$472 billion. Furthermore, the government made progress in the establishment of the Sovereign Wealth Fund (now the Mutapa Investment Fund). On the 20th of September 2023 President Mnangagwa through SI 156 of 2023 renamed and began the operationalisation of the Mutapa Investment Fund (MIF) (Veritas, 2023). By November 2023, a board for the fund was appointed (Moyo, 2023). On 15 March 2024, seven (7) more entities were added to the list of companies whose shares will be part of the investment fund through SI 51 of 2024. The total number of vested companies managed by the MIF is now 30. In June 2024, the chief investment officer presented that “The Mutapa fund has a portfolio of around 66 companies including intermediary holding companies, operational and dormant entities, listed and state-owned enterprises” (Mhlanga, 2024). The vested companies are clustered into sectors with Infrastructure, Natural Resources, Finance Services and Transport, each containing five (5) companies (See Figure 3 below).

Several tax widening measures were also introduced in the 2024 Budget announcement and effected at the start of 2024 (Lexology, 2024). These are shown in the textbox below.

- Sugar Tax: 0.01 cents per gram of additional sugar in beverages (down from the initial 0.02 cents).

- IMTT: 1% on outbound payments made using foreign currency from the RBZ auction or interbank market.

- Mining & Quarrying Levy: 1% of gross sales (export or local) of lithium, black granite, quarry stones, and uncut/cut dimensional stones.

- Corporate Tax Increase: 24% to 25%.

- Wealth Tax: 1% on residential property exceeding USD 250,000 (excluding primary residence), capped at USD 50,000.

- VAT Registration Threshold Reduction: USD 40,000 to USD 25,000 (bringing more entities under VAT).

- VAT Exemption Revision: Most basic goods are now VAT standard rated (except medicine, medical services, specific goods for the disabled, sanitary wear, fuel, and agricultural inputs).

- Special Capital Gains Tax on Mining Titles: 20% on transfer of mining rights within/outside Zimbabwe.

- Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax (DMTT): Ensures multinational enterprises with low-tax profits are taxed at a minimum 15% rate.

The government has spent a considerable amount of resources focused on improving infrastructure. In January 2024 the government adopted a new Road Development Program as a successor initiative to the Emergency Road Rehabilitation Programme (ERRP2) which lapsed at the end of 2023. The rehabilitation and construction of roads across the country have continued into 2024. There is no independent verification of the actual amounts spent to date on roads and the kilometres covered. According to the government, 50,000km have been rehabilitated out of the country’s estimated 84,000km of road network through its Emergency Road Rehabilitation Programme (ERRP2) since 2021 (Mazarura, 2024). The rehabilitation entails different kinds of work including resealing of roads, gravelling, re-gravelling, road grading, attending to gullies and wash-aways and the building of structures like bridges and interchanges. Flagship projects under this programme have included the Harare-Masvingo-Beitbridge rehabilitation where 474km out of the 580km of road have been rehabilitated and opened to the public; the rehabilitation of major roads within Harare; and the ongoing construction of Mbudzi Interchange.

The country continues to face a debilitating energy crisis due to old equipment at its Hwange power station and the low water levels on the Kariba Dam. The latter has led to limited power generation. At the time of writing this report government’s power utility company has issued a notice that there is limited power generation due to the breakdown at the Hwange Power Station. Current power generation is at 1300MW against a peak demand of 1900MW. The government expects that demand for power will grow to 5,000MW by 2030. In the meantime, the government has carried out a number of actions to alleviate the shortage of power including:

- Chrome miners, the largest consumers of power, have been advised to produce their own power (newZWire)

- Ongoing negotiations with India’s Eximbank to fix the aged generators in order to increase power production from the old units from 400MW to 840MW

- secured a US$50 million loan from Stanbic Bank to initiate the repowering of Hwange Power Station Units 1 to 6 (Bulawayo24)

- The introduction of the net metering program allows consumers to sell off excess electricity, generated mostly through solar, back to the power utility

However, policy-based constraints have limited private sector participation in generating power. The low tariffs currently in place are generally viewed as unsustainable for private sector involvement in energy markets. The net metering program mentioned is a great idea, but it has yet to take full effect.

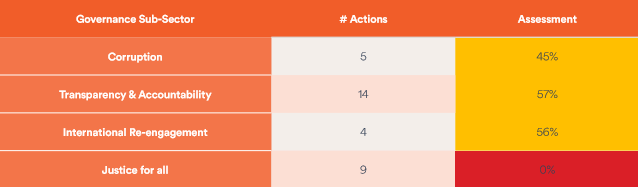

5.1.2 Governance

The Governance sector is made up of four (4) sub-sectors, Corruption, Accountability and Transparency, International Re-engagement and Justice for all. There is a total of 33 promises. A total of 32 actions related to this sector have been recorded since the 4th of September 2023. The Mnangagwa administration’s second term of office committed to a citizen-centric government. This has manifested through their actions in responding to citizen emergencies.

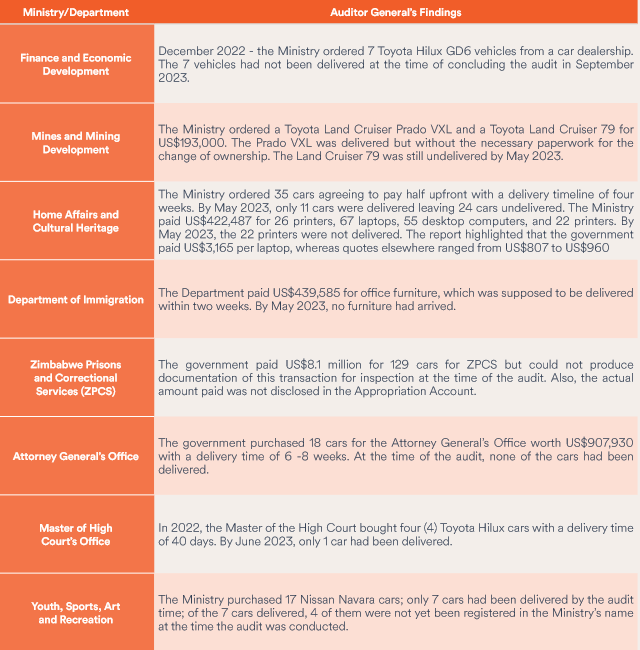

When it comes to dealing with corruption, allegations within and around the government continue to dent the reputation of the government. The former head of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) confirmed that corruption is costing the government and country at least US$1.8 billion annually mostly through illicit financial flows (VoaNews, 2024). Others argue that there is even an equal amount or more that is lost to corruption within the country without being siphoned out of the country. Notable allegations of corruption include the abuse of the Presidential Input scheme where two businessmen aligned to the ruling party secured the contract to supply 632 000 goats but were only able to supply 4,208. The court papers allege that the pair misrepresented themselves in the process of securing the contract. The businessmen mentioned above are still in prison pending trial. The Auditor General’s report of July 2024 revealed a number of potentially corrupt arrangements within the government (The Zimbabwe Mail, July 2024). These included:

The government has in the past faced challenges related to the levels or non-existence of transparency in procurement, especially when it comes to making decisions on who should supply goods and services to the government. There were allegations that the public tender system is porous and subject to manipulation. Several reports by the Auditor General have raised concerns about procurement procedures within government departments and state-owned enterprises (SoEs). The Auditor General’s reports are usually the main tool used for ensuring transparency and accountability. In the Veritas, (2023) report on the performance of SoEs, the Auditor General issued:

- fifty-seven (57) Unmodified/clean opinions

- eleven (11) Disclaimer of opinion

- ninety (90) Qualified opinions

- of which eighty-five (85) relate to non-compliance with the standards in particular IAS 8 – “Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors”, IFRS 13 – “Fair Value Measurements, IAS 16 – “Property, Plant and Equipment” and IAS 21 – “The Effect of Changes in Foreign Exchange Rates”

- four (4) were qualified for unsupported expenditure and suspense accounts.

- thirty-three (33) Adverse opinions and

- twenty-six (26) entities with conditions that may cast doubt on the entity’s ability to continue operating as a going concern.

According to the report, the number of entities that were up to date in terms of account submission has been gradually increasing since 2019. In 2019 only 103 entities were ready but in 2023 the number has increased to 119. The number of entities being audited has increased from 137 in 2019 to 163. However, it is not all rosy; the audit report shows that there was an increase in reported issues on governance from 170 to 310. Furthermore, the report notes the following:

- instances of weak internal controls as evidenced by unsupported expenditure

- non-alignment of accounting policies and processes with reporting framework (accounting standards)

- outdated accounting manuals

- non-compliance with tax laws and regulations

- non-performance of bank reconciliations

- absence of internal audit arrangements and,

- late submission of financial statements creating gaps for accountability and resulting in limitation of scope due to lapse of time documents cannot be located.

Unfortunately, there is no corresponding report (2023) on the performance of Ministries. However, the report on (SoEs suggests that Ministries are not providing adequate oversight support.

There are cases of corruption within local municipalities and urban land management. In dealing with corruption in urban land management systems the government, following a blitz against land barons, close to 4,000 suspects and squatters have been arrested across the country with 985 convictions in the courts, while 3,360 cases are pending trial since January 2024 in an exercise meant to clamp down on the proliferation of illegal settlements (Moyo, 2024). The government has also started consultations in December 2023 to incorporate corruption studies into the school curriculum (Madzianike, 2023).

The budget allocations towards the fight against corruption have been limited. In October 2023, the government through the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (PRAZ), (2024) launched a new procurement system called electronic Government Procurement (e-GP). The completion of the new system is expected to contribute towards reduced incidences of corruption. Furthermore, as a continuation of practice that began in the previous term, the President signed 2024 performance contracts with ministers, senior civil servants and heads of state-owned enterprises (APAnews, 2024). The nature of the key performance indicators against which the performance would be assessed were, however, not made widely available to the public.

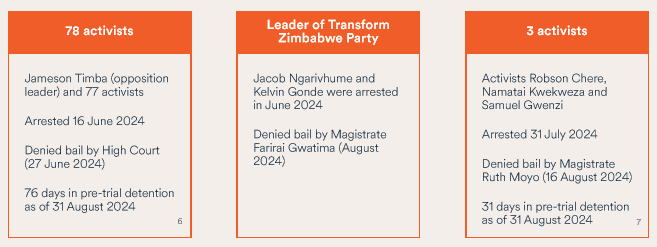

One of the government’s commitments through NDS1 under Governance is to improve the justice system. However, this is where the government has probably failed the most. There has been an increase in the number of arrests of political actors (activists and politicians). Whilst the police have the right to arrest anyone suspected of having committed a crime the courts are obligated to ensure that the suspects are treated fairly.

One of the conditions for the fairness rule is to ensure that suspects are provided with bail whilst awaiting trial. It has become routine for the Magistrates Courts to deny bail to political actors.

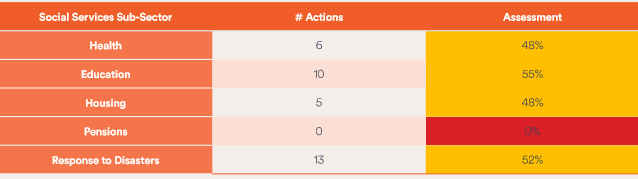

5.1.3 Social Services

Perhaps the worst dimension of the Zimbabwe crisis has been the collapse of the social service delivery system at both national and local levels. There has been under-investment in the public health and education delivery sectors. An average of 84% of enrolled children complete primary education and 58% go on to complete high school. The El Niño-induced drought could be the latest amongst many other factors that have influenced the increase in the number of school dropouts. The latest Zimbabwe Livelihoods Assessment Committee (ZimLAC) 2024 Rural Livelihoods Assessment report states that 25,8 % of school-going children in Mashonaland Central are not attending school. Matabeleland North and Matabeleland South follow closely with 25,2 % and 25,1% of children out of school, respectively (UNICEF, 2024). Another report by the Education Coalition of Zimbabwe claims that 2.7 million children are out of school (The Zimbabwe Mail, July 2024).

Health delivery is uneven across Zimbabwe. There is a thriving private sector-led medical services sector which can easily compete with what is available outside the country. However, this sector is very small and only caters for a minority with access either to medical insurance or the means to pay. Public health facilities have been in constant decline for more than a decade. There are a number of news reports of citizens crossing the border to secure what may be considered basic medical attention, such as giving birth. Pensions collapsed at the time of hyperinflation. There has been limited to non-existent delivery of low-cost housing stocks. Since September 2023, three (3) housing projects have been completed: 17 core houses in Binga, Dzivarasekwa Flats and civil servant houses in Lupane.

Tracking social service delivery can be a daunting task. The needs of a country, especially of an underdeveloped one like Zimbabwe cannot be resolved in one year. Tracking budget allocations provides a way to determine if the government is on its way to achieving set goals within NDS1 and also according to the Sustainable Development Goals framework. The government is already a signatory to a number of African Union-led frameworks for ensuring the development and improvement of social service delivery in member countries.

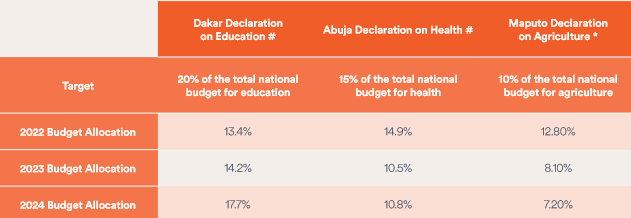

The government signed a number of declarations where it is supposed to allocate 20% of its budget towards education, 15% towards health and 10% towards Agriculture. The Table below demonstrates that the government has since 2022 missed the targets for education, health and agriculture (food security).

Some of the notable actions recorded under health are that on the 29th of October 2023, the Government acquired Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machines for Mpilo Hospital in Bulawayo and Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals in Harare (Muchetu, 2023). On the 25th of March 2024, Zimbabwe signed an MoU with Belarus for the training of doctors and supply of medical drugs and equipment among others. The government built a community health centre in Chimanimani (NMS Infrastructure Limited, 2024) which was commissioned in June 2024.

In Education, the government replaced the continuous assessment learning activities (CALA) with the Heritage-based Education curriculum framework. According to the government, the new curriculum will transform the education system to produce citizens with relevant skills, applied knowledge, values and dispositions that are key to national development, beginning with the communities they serve.

As a response to disasters and to ensure food security in the country, one of the commitments by the government is to promote resilience and sustainable agriculture, however, this has been disrupted by the effects of El Niño induced drought. The government has employed several actions towards risk/disaster management. This has been evident through setting aside ZWL$44 billion to facilitate the delivery of 71,500 tonnes of maize, sorghum and millet to about 2.7 million hungry people in 59 districts surveyed under the national assessment of the crop situation in the country. (Chronicle, March 2024). The government also put in place a range of measures to ensure food security during this period (The Herald, March 2024) which included:

- the purchase of local grain at an import parity price of US$390 per tonne to mop up excess local grain

- duty waiver on the importation of rice and potato seed

- importation of genetically modified maize for stock feed with strict conditions for milling and distribution

- duty-free importation of maize, rice and cooking oil by households from July 2024, and

- the re-activation of the Grain Mobilisation Committee.

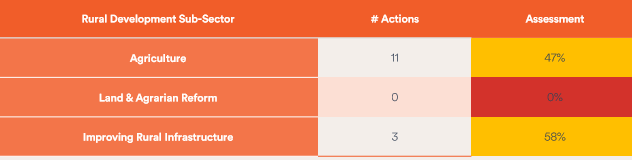

5.1.4 Rural Development

The Rural Development sector focuses on Agriculture, Land and Agrarian Reform and Improved Rural Infrastructure. The government recognises the central role that agriculture plays in the economy. The Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development highlights that agriculture employs about 70% of the population, and approximately 60% of all raw materials for industry and 45% of the country’s exports are of agricultural origin (Ministry of Lands, 2024). However, the government did not allocate 10% of its overall budget towards agriculture in 2023 and 2024 (see Table 12 above) as per the provisions of the Maputo Declaration (renewed at Malabo in 2013) which it is a signatory.

The Government’s commitments under Rural Development through the NDS1 include upscaling climate-smart agricultural practices, rural land delivery for rural housing, enhancing community water supply through the drilling of boreholes and the development of innovation hubs to aid rural industrialisation. The climate-smart practices are focused on the Pfumvudza/Intwasa initiative. According to Manomano (2023) by October 2023, farmers had prepared 3,5 million Pfumvudza/Intwasa plots for the 2023/2024 agriculture season. Out of the 3,5 million plots, 2.4 million plots across 150,000 ha had been prepared for maize, 572,000 plots on 38,000ha for sorghum and pearl millet and 239,000 plots on 16,000 ha had been prepared for groundnut and soya bean production. According to the Ministry, the irrigated area has increased from 173,000 ha in 2020 to 217,000 ha. The government intends to grow the area under irrigation to 350,000 ha by 2027 (Chitumba, 2023). Crop production has improved since 2017. The most dramatic has been the growth in the production of soya beans (200%), wheat (1438%) and sorghum (295%).

Our tracker has recorded 14 actions to date under this sub-sector. November 2023, saw the completion and commissioning of Gunguhwe Bridge in the Gokwe North District (Mupanedemo, 2023). As of 22 November 2023, the government reported that over 1.9 million farmers have been trained under the climate-proofed Presidential Inputs Supply Scheme (Chingwere, 2023) in efforts to upscale climate-smart agricultural practices. In early January 2024, the government distributed 62.5 tonnes of sorghum seed to farmers in Makoni district in Manicaland and other parts of Mashonaland West (Ngwenya, 2024) as part of efforts to encourage farmers to plant short-season crop varieties to mitigate the challenges brought about by El Niño.

However, there are still some challenges. The government still retains the responsibility of buying the majority of cereals produced by farmers. In the year under review, the purchasing authority delayed payments due to farmers. According to a Bulls & Bears (May 2024) report government owed farmers US$20 million for wheat that was delivered in the 3rd and 4th quarters of 2023. These delays spread to other crops where the government is the major buyer such as maize. In tobacco, the government shifted from the 2022/2023 position of 85/15 where farmers could retain 85% of their earnings in foreign currency. In the 2023/2024 season, the government moved to 75/25 where farmers can only retain 75% of their earnings. The delays in effecting payments and measures which limit the amount of foreign currency available to tobacco growers can only serve to limit the capacities of affected farmers. Furthermore, the agriculture sector, since 2003 (fast track land reform) has struggled to attract private sector investments, especially banks. There are some exceptions, such as contract farming models for tobacco and facilities for horticulture farmers. However, there have not been significant land tenure-focused reforms to create a property market which can attract funding. The Global Compensation Agreement for former large-scale farmers potentially provides a solution towards the resolution of the contestation around land ownership that emerges in the aftermath of fast-track land reform.

6.0 Conclusion: Where is Zimbabwe Headed?

What then shall we make of the government’s performance? Usually, there are two perspectives- one that sees everything as progressive and the other that thinks otherwise. Zimbabwe is thus either a good story to tell or just another underperforming economy run by kleptocrats. The truth is usually somewhere in between. The subsection below discusses in more detail these perspectives.

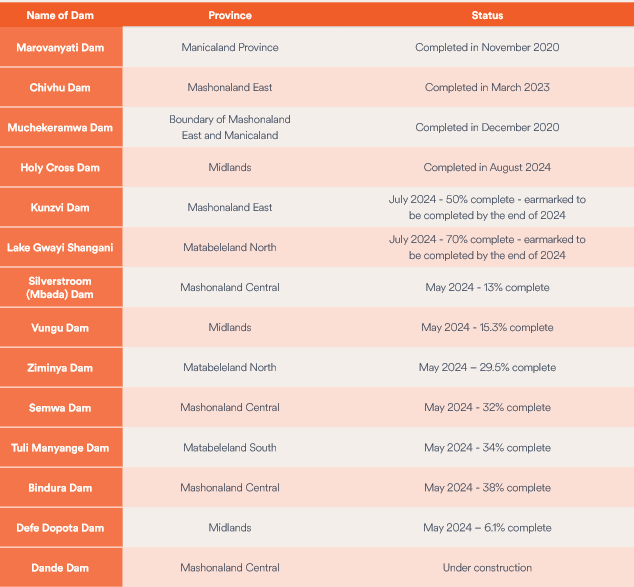

6.1 A Good Story to Tell- The Infrastructure Revolution

Prior to 2017 grand infrastructure projects were very few. The GoZ had completed the Tokwe Mukosi Dam in May 2017, there was on-and-off work on the Harare to Bulawayo dualisation project and there was the rehabilitation of the Hwange power station. The government (Second Republic) has spent significant amounts of money on dam construction and on building and maintaining roads. To date, the government has been working on the rehabilitation of 14 dams across the country. Of the 14 dams, the rehabilitation of four (4) of these dams – Marovanyati, Chivhu, Muchekeramwa and Holy Cross Dams has been completed and they have been commissioned. The table below provides details on the progress made in this area.

The road rehabilitation (paving and repaving) is another site of progress. To date, major roads within Harare have benefitted from government intervention. Beyond roads, there is another good story-the increase of land under irrigation. Climate change has disrupted agriculture to the extent that rain-fed/dependent cropping practices are no longer reliable. The African Union’s Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) had, way back in the early 2000s called for member states to increase the land under irrigation as one of the strategies to adapt to climate change. The Zimbabwean situation is one of recovery from previous damage carried out during the ‘jambanja’ era. The government (with some private sector participation) has increased the land under irrigation significantly.

6.2 Grand Rhetoric

6.2.1 Zimbabwe is Open for Business

The President’s ‘open for business’ mantra has been the claim that the country is open for business suggesting the ease of setting up and doing business and a renewed attempt at attracting foreign direct investment. Zimbabwe scored 38.2% on the Index of Economic Freedom. The Zimbabwean economy is characterised by instability and policy volatility, both of which are hallmarks of excessive government interference and mismanagement that have undermined the country’s economic potential. The government has made regular use of statutory instruments and temporary presidential powers to alter legislation impacting economic policy. In the year under review alone, the government changed the local currency, introduced measures that bar manufacturers from trading with so-called ‘informal traders’ and changed the portion of foreign currency that exporters can retain.

It may be that the government, through ZIDA, has resolved the speed with which one can register a business but policy-related inconsistencies and constraints remain. The bureaucratic red tape remains intact and that has been Zimbabwe’s challenge in almost every sector.

6.2.2 On Mega Infrastructure Projects

State-owned media narratives in many instances suggest that the country is on course to achieve middle-income status by 2030. The rhetoric around mega-development projects most often includes projects that were merely launched on paper. State-owned publications like the Herald have run with headlines such as ‘Govt Implements record 7,000 Projects’ (Murwira, 2023) and ‘Second Republic completes more than 7,000 projects: Govt’ (Razemba, 2024) all in a space of 12 months. A performance feat like that would make the government of Zimbabwe rank as one of the most effective. However, further examination reveals the number includes projects or initiatives that have just been launched and are yet to be implemented. The government communications team instead of referring to one big project, subdivides some of these into minuscule bits to give the impression of a high number of projects. Take for instance the real good work around roads. Instead of consolidating all this under one big project ‘road rehabilitation’ each road is treated as a separate project in the report.

6.3 A Shrinking Space

There is a new level of intolerance of dissent in Zimbabwe. For the first time since independence Zimbabweans are actually afraid of demonstrating or protesting any government action. The government has, without dramatically changing any laws, made it so difficult for opposition politicians and activists to immediately seek relief from the courts. Many have been arrested and denied bail. It is not immediately clear to many the crime committed by Timba and 77 others who were arrested on the 16th of June 2024 for holding an authorised gathering. They were denied bail, and their trial is yet to begin. Many others have been arrested and denied bail. The wheels of justice move very slowly. The possibility of a new Non-Governmental Organisation law replacing the current Private Voluntary Organisations Act [Chapter 17:05] has led to many organisations engaging in self-censorship – the fear of being singled out for de-registration. The commitment to justice that is clearly articulated in NDS1 has been violated several times over by the government’s refusal to ensure that Zimbabweans are treated equally before the courts of law. Furthermore, the government of Zimbabwe has probably missed out on the relationship between civil liberties and being ‘open for business’. Civil society organisations are a huge contributor to a thriving economy through the creation of jobs, use of facilities and payment of taxes.

6.4 How about the Multifaceted Crisis?

Unfortunately, various dimensions of the crisis have mutated into new problems. The country faces an urgent crisis of livelihoods in both the urban and rural areas. According to the World Food Program, 4.1 million people face food insecurity. This is out of the country’s population of 16.6 million (Langa, 2024). The 2024 food shortages are mostly due to the El Niño induced drought. However, the country has struggled with food insecurity for a much longer period. For instance, in the October-December 2022 period, even before the height of the lean season, which usually finished in March, 3 million people were in crisis or worse representing about 20% of the total population (FSIN, 2023).

The economic dimensions of the crisis remain in place despite several attempts at reforms. The country remains in some form of economic isolation. It cannot attract international capital to revitalise the private sector and infrastructure development. The government has yet to effectively address the outstanding debt issue. For the record, Zimbabwe’s total consolidated debt amounts to US$17.5 billion. The debt owed to international creditors stands at US$14.04 billion, while domestic debt comes to US$3.4 billion. Debt owed to bilateral creditors is estimated at US$5.75 billion, while debt to multilateral creditors is estimated at US$2.5 billion (AfDB, 2023). The country is in arrears in terms of servicing the debt. Furthermore, some aspects of sanctions were lifted by the United States of America government, but ZDERA remains in place. There are not enough formal sector jobs being created. The country has a very young population and a thriving tertiary education sector. Unfortunately, most of the graduates remain unemployed or under-employed (overqualified for jobs that they eventually take). The rate of out-migration has not slowed down. Health professionals continue to emigrate in search of greener pastures.

Social service delivery remains constrained due to; (i) ineffectiveness of central and local authorities, (ii) sub-optimal budget allocations towards social service delivery and (iii) abuse of public resources. The governance crisis remains fully intact. The country has mostly been run using statutory instruments and temporary presidential powers. In the process, the legislative arm of government has been denied the opportunity to meaningfully scrutinise proposed laws. Furthermore, despite the widespread acknowledgement that corruption is rampant, very little is being done to effectively deal with it. Many alleged offenders have close ties with powerholders, and they have often been released except for a few. There is no national compact to deal with corruption. The country is yet to create a platform for consensus building. It is still defined by a winner-take-all mentality, and, in the process, toxic partisan-based polarisation dominates public discourse.

7.0 References

- AfDB. (2023, Jul 11). Zimbabwe hosts 5th structured dialogue on debt with creditors. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/zimbabwe-hosts-5th-structured-dialogue-debt-creditors-62905

- APA News. (2024, March 15). Mnangagwa signs performance-based contracts with ministers. https://apanews.net/mnangagwa-signs-performance-based-contracts-with-ministers/

- Auditor General. (2024). Database of audited reports of ministries and departments. Report of the Auditor-General for the financial year ended December 2023 on Appropriation Accounts Finance and Revenue Statements and Fund Accounts. https://www.auditorgeneral.gov.zw/downloads/category/3-ministries-and-departments

- Bulawayo24. (2024, June 23). US$450 million to repower Hwange Units 1-6. https://bulawayo24.com/index-id-news-sc-national-byo-242885.html

- Bulls & Bears. (2024, May 17). Govt fails to pay wheat deliveries. https://bullszimbabwe.com/govt-fails-to-pay-for-wheat-deliveries/

- Chidakwa, B. (2023, October 10). Unpacking the new Skills Audit, Development Ministry. The Herald. https://www.herald.co.zw/unpacking-new-skills-audit-development-ministry/

- Chingwere, M. (2023, Nov 22). Enough fertilisers secured for summer cropping season. The Herald https://www.herald.co.zw/enough-fertilisers-secured-for-summer-cropping-season/.

- Chitumba, P. (2023, September, 3). Over 200 000 hectares now under irrigation. The Herald. https://www.herald.co.zw/over-200-000-hectares-now-under-irrigation/

- Chronicle. (2024, March 5). COMMENT: Grain movement to all food-insecure people must be expedited. https://www.chronicle.co.zw/comment-grain-movement-to-all-food-insecure-people-must-be-expedited/

- Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI). (2023). The CZI state of manufacturing survey. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YIuLp_Tw8_2Og8ADSnR37BsdTgHND0p-/view

- Debt Justice. (2024). Zimbabwe Profile. https://debtjustice.org.uk/countries/zimbabwe

- FSIN. (2023). Food Security Information Network. Italy. https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/s1rnfpf

- Helliker, K., & Murisa, T. (2020). Zimbabwe: continuities and changes. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 38(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2020.1746756

- Index of Economic Freedom. (2023, October). Economic Freedom Country Profile: Zimbabwe. https://www.heritage.org/index/pages/country-pages/zimbabwe

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Zimbabwe and the IMF Profile. https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ZWE

- Jowah, E. (2023). Citizens’ Perceptions and Expectations: 2023 Survey Findings Report. https://backend.sivioinstitute.org/uploads/2023_Citizens_Perceptions_and_Expectations_b9fa69f13a.pdf

- Langa, V. (2024, Feb 12). Zimbabwe’s food needs might increase in 2024 as 2.7 million people face hunger. The Africa Report. https://www.theafricareport.com/334585/zimbabwes-food-needs-might-increase-in-2024-as-2-7-million-people-face-hunger/

- Lexology. (2024). WTS Global. Zimbabwe tax measures for 2024- Domestic resource mobilization through tax. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=dc580870-6799-4c44-9ec2-4586aedd0a16#:~:text=Sugar%20Tax%3A%200.02%20cents%20per,and%20uncut%2Fcut%20dimensional%20stones

- Madzianike, N. (2023, Dec 20). NEW: Govt to introduce corruption studies in school curriculum. The Sunday Mail. https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/new-govt-to-introduce-corruption-studies-in-school-curriculum

- Manomano, P. (2023, October 30). Farmers prepare over 3,4 million Pfumvudza plots. The Herald https://www.herald.co.zw/farmers-prepare-over-34-million-pfumvudza-plots/

- Mazarura, T. (2024, July 14). The dual impact of Zim’s Emergency Road Rehabilitation Programme. The Sunday News. https://www.sundaynews.co.zw/the-dual-impact-of-zims-emergency-road-rehabilitation-programme/

- Mhlanga, T. (2024, June 16). Mutapa portfolio grows to 66 companies. Zimbabwe Independent. https://www.newsday.co.zw/theindependent/business/article/200028358/mutapa-portfolio-grows-to-66-companies

- Mhlanga, T., & Chikandiwa, H. (2024, April 5). US$575m war chest to anchor new currency. Newsday. https://www.newsday.co.zw/theindependent/local-news/article/200025222/us575m-war-chest-to-anchor-new-currency

- Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development. (2024). Zimbabwe irrigation Investment Prospectus. https://www.agric.gov.zw/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IRRIGATION-PROSPECTUS-2.pdf

- Moyo, A. (2023, November 7). Mutapa Investment Board Appointed. The Herald https://www.herald.co.zw/mutapa-investment-board-appointed/

- Moyo, B. (2024, Feb 14). Over 3 500 illegal settlers arrested in countrywide crackdown. Chronicle.https://www.chronicle.co.zw/over-3-500-illegal-settlers-arrested-in-countrywide-crackdown/

- Muchetu, R. (2023, Oct 29). Mpilo, Pari secure first-ever MRI scans. The Sunday News. https://www.sundaynews.co.zw/mpilo-pari-secure-first-ever-mri-scans/

- Mupanedemo, F. (2023, Nov 3). Gunguhwe Bridge opening brings relief to villagers. Chronicle. https://www.chronicle.co.zw/gunguhwe-bridge-opening-brings-relief-to-villagers/

- Murisa, T. & Chikweche, T. (2015). Beyond the Crisis: Zimbabwe’s prospects for transformation. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293531148_Beyond_the_CrisesZimbabwe’s_Prospects_for_Transformation Weaver Press.

- Murisa, T. et al. (2023). Five Years of Progress or Stagnation: An Assessment of the Government’s Performance and Commitment to their Manifesto Promises for 2018 – 2023. https://backend.sivioinstitute.org/uploads/2023_SIVIO_Barometer_dd0db8bfc5.pdf

- Murwira, Z. (2023, June 7). Govt implements record 7 000 projects. The Herald. https://www.herald.co.zw/govt-implements-record-7-000-projects/

- Newsday. (2024, August 23). Zimbabwe to achieve targeted metric tonnes of winter wheat. https://www.newsday.co.zw/agriculture/article/200031364/zimbabwe-to-achieve-targeted-metric-tonnes-of-winter-wheat

- NewZimbabwe. (2024, February 23). Zimbabwe launches digital investment licensing system to attract investors. https://www.newzimbabwe.com/zimbabwe-launches-digital-investment-licensing-system-to-attract-investors/

- newZWire. (2024, June 12). Government tells power-hungry ferrochrome producers: Produce your own electricity, ease pressure on ZESA. https://newzwire.live/govt-tells-power-hungry-ferrochrome-producers-produce-your-own-electricity-ease-pressure-on-zesa/

- Ngwenya, P. (2024, Jan 12). Government urges farmers to plant short-season crops due to low rainfall. Chronicle. https://www.chronicle.co.zw/government-urges-farmers-to-plant-short-season-crops-due-to-low-rainfall/

- NMS Infrastructure Limited. (2024, June 22). VP commissions Runyararo Health Centre Zimbabwe. https://www.nmsinfrastructure.com/blog/2024/6/22/jd5vud8rm4xajc6zf9rp0henwxter0

- PRAZ. (2024). eGP System. https://egp.praz.org.zw

- Razemba, F. (2024, July 3). Second Republic completes more than 7 000 projects: Govt. The Herald. https://www.herald.co.zw/second-republic-completes-more-than-7-000-projects-govt/

- Sibanda, G. (2024, April 4). RBZ Unveils New Currency. The Herald. https://www.herald.co.zw/rbz-unveils-new-currency/

- SIVIO Institute. (2024). SIVIO Institute Website. https://sivioinstitute.org/

- SIVIO Institute. (2024). ZIMCITIZENSWATCH. https://zimcitizenswatch.org/

- The Herald. (2024, March 13). Cabinet institutes measures to guarantee food security for all. https://www.herald.co.zw/cabinet-institutes-measures-to-guarantee-food-security-for-all/

- The Zimbabwe Mail. (2024, July 3). Zimbabwe battles increased school dropouts. https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/education/zimbabwe-battles-increased-school-dropouts/

- The Zimbabwe Mail. (2024, July 12). Damning Audit Report: Corruption Scandal Rocks Zimbabwean Government. https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/zimbabwe/damning-audit-report-corruption-scandal-rocks-zimbabwean-government/

- UNICEF. (2024). Zimbabwe Livelihoods Assessment Report 2024. https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/reports/zimbabwe-livelihoods-assessment-report-2024

- Veritas. (2018). UNABRIDGED Transitional Stabilisation Programme Oct 2018-2020. https://www.veritaszim.net/node/3307

- Veritas. (2021). National Development Strategy 1 January 2021 – December 2025. https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/NDS.pdf

- Veritas. (2023). AG report 2023 on state-owned enterprises and parastatals. https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/AG%20Report%202023%20on%20State%20Owned%20Enterprises%20and%20Parastatals%20.pdf

- Veritas. (2023). The 2024 National Budget. Originally published by the Ministry of Finance. https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/The%202024%20Budget%20Statement.pdf

- Veritas. (2023). SI 2023-156 Presidential Powers (Temporary Measures) (Investment Laws Amendment) Regulations, 2023 (Mutapa Fund). https://www.veritaszim.net/node/6573

- Veritas. (2024). Statutory Instrument 51 of 2024. Sovereign Wealth Fund of Zimbabwe (Amendment of Fourth Schedule) Notice, 2024 https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/SI%202024-051%20Sovereign%20Wealth%20Fund%20of%20Zimbabwe%20%28Amendment%20of%20Fourth%20Schedule%29%20Notice%2C%202024.pdf

- Vhumbunu, C. H. (2022, May 3). Doing business in Zimbabwe: A 2022 synopsis of the business, policy, legal and regulatory landscape. African Association of Entrepreneurs. https://aaeafrica.org/zimbabwe/doing-business-in-zimbabwe-a-2022-synopsis-of-the-business-policy-legal-and-regulatory-landscape/

- VoaNews. (2024, May 9). Senior Zimbabwean Official says corruption is hurting economy. https://www.voanews.com/a/senior-zimbabwean-official-says-corruption-hurting-economy/7604865.html

- World Bank. (2023). GDP (current US$) – Zimbabwe. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZW

- ZANU PF Patriots. (2018). ZANU PF Election Manifesto 2018. Accessed August 2024. zanupfpatriots.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Zanu-PF_election_manifesto_2018.pdf

- Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education. 2018 National Critical Skills Audit Report. https://www.zimche.ac.zw/blog/2018-national-skills-audit-report/

- ZIMCODD. (2024). Health and Education Situational Report – February 2024. https://zimcodd.org/storage/2024/03/Health-And-Education-Situational-Report-February-2024.pdf

- ZIMSTAT. (2019). 2019 Labour Force and Child Labour Survey. https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Labour-Force-Report-2019.pdf

- ZIMSTAT. (2021). 2021 Fourth Quarter Quarterly Labour Force Survey. https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/publications/Economic/Employment/Fourth_Quarter_Labour_Force_Report_2021.pdf

- ZIMSTAT. (2024). 2024 First Quarter Labour Force Survey Report. https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/LabourForce/2024_First_Quarter_QLFS_Report.pdf

- ZIMSTAT. (2024, March). Zimbabwe’s External Trade. Report published in March 2024. https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/Trade/EXTERNAL_TRADE_03_2024.pdf

- ZIMSTAT. (2024). Labour Statistics. Report published in 2019, Q1 2024 https://www.zimstat.co.zw/labour-statistics/