INTRODUCTION

The Malawi Congress Party (MCP) was elected to office on June 28, 2020. This was after the nullification of the 2019 presidential results based on electoral irregularities. MCP made more than 204 promises through its manifesto[1]. Where are we four (4) years down the line and with elections earmarked for September 2025? Promising is one thing, but delivering on the promises means everything for a country struggling to attain a middle-income status and fighting higher levels of poverty and adverse macroeconomic conditions.

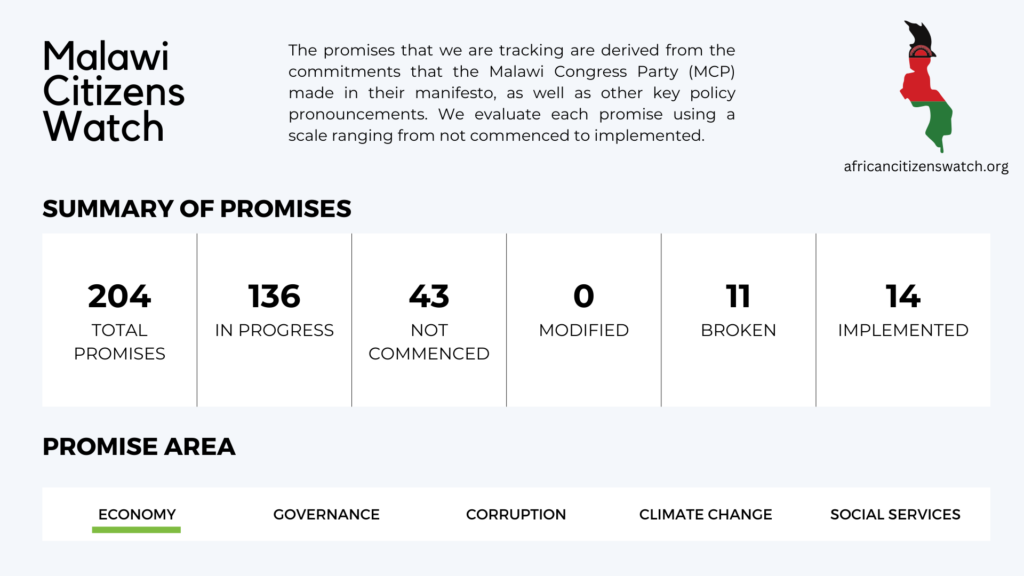

Since 2020, SIVIO Institute (www.sivioinstitute.org) has been tracking the progress of the MCP in fulfilling its electoral promises and other major policy pronouncements while in office through the Malawi Citizens Watch Tracker. The tracker seeks to provide a factual assessment of the progress in fulfilling promises made by the MCP regime. A quick assessment of the promises and actions taken on them by the government reveals that as of February 2025, out of the 204 promises, 14 (representing 7%) had already been completely fulfilled by the end of 2024[2]. There was also progress made on 136 (representing 66%) of the promises, but these had not been fully met. Despite this notable progress, 43 promises (representing 2%) have not commenced, and 11 promises have been broken (representing 5%).

While progress has been made in various sectors, including climate change, social services, and governance, there remain major challenges around the fulfilment of economic promises faced by President Chakwera and his government.

THE TRACKING METHODOLOGY

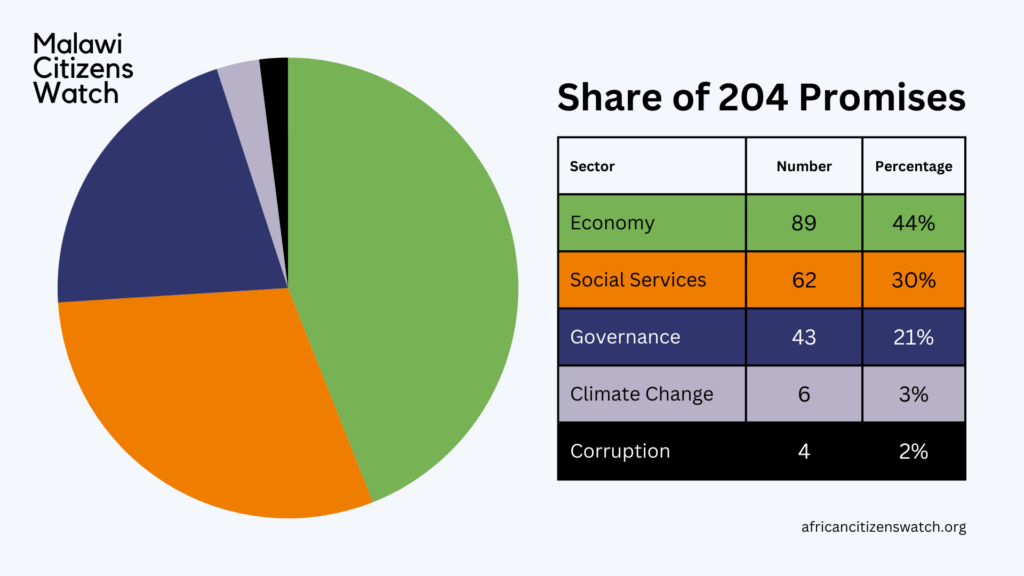

Malawi Citizens Watch Tracker was developed with promises extracted from the 2019 MCP manifesto. The promises are categorized into five (5) sectors, namely, Economy, Governance, Corruption, Climate Change, and Social Services (see Fig 1).

Despite having won as Tonse Alliance[3], it is MCP that was on the ballot and as such SIVIO Institute opted to only track promises made by the regime recognised by the constitution of Malawi, MCP. The approach involves tracking actions that the government has taken to fulfil the promises made. A final 5-year assessment shall objectively assess all the actions taken and the overall performance of the government at the end of its term of office.

Actions are recorded from reliable sources, including government Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs), trusted newspapers, trusted online and media platforms, and international organizations’ websites. The actions are triangulated with various sources for fact-checking, and a thorough review is done before uploading them on the Malawi Citizens Watch Tracker.

SNAPSHOT ANALYSIS OF THE PROGRESS ON THE PROMISES AS OF 2024

The four (4) years of President Chakwera’s term of office have been a mixed bag in terms of performance and fulfilment of promises made. The most significant promises made that the platform tracks have been around the economy, which constitutes 44% (58/204) of the total promises made. To date, 10% (9/58) of these promises have been completed. The government has, in line with its promises, made upgrades to the M1 highway, developed a 2022-2027 Strategic Plan for the Ministry of Mining in line with its promise to develop a comprehensive Mining Strategy, developed a Tourism Marketing Strategy, raised the zero-rated Pay As You Earn (PAYE) tax threshold from MK35,000 to MK100,000, and finalized geo-mineral resource mapping and developed a comprehensive exploitation plan, among other things.

Some positive strides have also been made with respect to the economy, even though the promises in these areas are yet to be fully fulfilled. The government has made progress on 60 of the 89 (67%) promises under the economy sector. Notably, the road network system in the capital city of Lilongwe has been improved, and the city has a new look (in line with the promise to improve the design of urban or residential road networks). Donors and Development Partners also signalled a resumption of direct budget support based on restored confidence in the regime. This is a massive win for a country that faces persistent budget deficits. There were also some prospects of economic turnaround through the National Economic Empowerment Fund (NEEF), which has been disbursing loans to Malawians through various loan products, the recent one being farm input loans[4] in line with the promise to strengthen agro-value chains to improve access to finance and markets for farmers.

However, a key promise that the government has failed to keep during this period has been around reducing the level of domestic and external debt from MK 3.5 trillion, when it came into office, to less than MK 1 trillion within the next five years. As of June 2024, the government indicated that domestic and external debt stood at just over K15 trillion, which amounted to 81% of the projected FY2024/25 GDP (Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, 2024). This rising debt has had a knock-on effect on the economy, which includes rising inflation, reaching a maximum of 35% despite the government’s promise to keep inflation at a single digit[5]. Sadly, the rise in inflation was further exacerbated by food components due to poor harvests as a result of cyclones. This meant that money lost value, and Malawians had to dig deeper into their pockets to survive. The local currency also lost value and reached unprecedented levels of MK1,800 to US$1 on the official market, with parallel markets reporting as high as MK3,000 to US$1. For a country that imports more, the weakening currency meant rising imported inflation on essential commodities like food, medicines, fertiliser, etc and this affected efforts to fulfil promises on agriculture and food security and health. The weakening currency is also a sign of low foreign reserves and trade imbalances[6]. As a result, Malawi faced disturbed importing, including fuel supply and long queues and sleeping at fuel stations became a norm, which led to the breaking of the promise of ensuring that the country has adequate production, supply, and stock of petroleum fuels at all times.

Beyond the economic sector, the government made some relatively significant strides in the other sectors. Under social services, which takes up 30% of the total promises, the government has fully implemented one promise, the reintroduction of Junior Certificate Exams. Progress has, however, been recorded on 68% (43 of the 62) of the promises. Notably, the government made progress on providing decent housing to all personnel serving in the health, military and police, addressing lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity, operationalizing the National Action Plan on persons with albinism, and pursuance of the UNAIDS 2014 build strategy dubbed as the 90-90-90 which targets to ensuring that 90% of people living with HIV know their status, 90% of the people diagnosed with HIV are put on treatment, and 90% of the people on treatment achieve an undetectable viral load. However, the government has yet to make progress on 16 of the 62 promises (25%). Some of these promises are establishing three world-class specialized secondary schools for youth selected from a rigorous and multi-faceted assessment, introducing social cash transfers for all persons with albinism, and building Special Needs Learning Centers (SNLCs) in every council to cater for kindergarten, primary and secondary schools with boarding facilities, among others.

Apart from Economy and Social Services, there has also been notable progress under Governance, which makes up 21% of the total promises. The government has fully implemented 5 (12%) of the 43 promises made. Notably, the government reviewed the Land Act to protect Malawian ownership of land, operationalized the Access to Information Act, and established a School of Diplomacy. Progress has also so far been registered on 59% of the promises made. Some of the key promises on which progress has been made include sustenance of Malawi’s diplomatic relations, strengthening of border posts, comprehensive audit of local governments, and presidential appearance before Parliament to enhance accountability and transparency. Despite this progress, four (4) (9% of Governance promises) have been broken, and nine (9) (20% of Governance promises) have not commenced. Notably, presidential powers in public appointments were not reduced, and the presidential convoy was not reduced as well. Promises yet to be commenced include the decongestion of prisons through community service programmes and the establishment of a new Police Academy in Lilongwe.

Climate Change and Corruption are the sectors with the smallest number of promises, 3% and 2% of the total promises, respectively. Under climate change, progress was registered on 4 of the 5 promises (representing 80%), and the only promises on which no progress was recorded are finalization and implementation of the National Climate Change policy framework. On the other hand, progress on 3 of the 4 promises (representing 75%) under Corruption was registered. However, the promise of a corruption-free, efficient, effective and responsive government anchored in the culture of rule of law and constitutionalism was broken even though initially positive progress was recorded.

4.0. MORE ON FUEL CRISIS

Historical overview

The fuel crisis in Malawi (a country that does not produce its oil) is nothing new. The crisis can be traced back to the first post-independence regime of Hastings Kamuzu Banda. During the Kamuzu era, Malawi faced fuel shortages in the late 1970s and early 1980s due to the Mozambican war, which disturbed supply chains[7][8]. When Bakili Muluzi was elected into office in 1994, he faced similar challenges. In 1998, Malawi faced a forex shortage due to the Balance of Payments deficit, and this led to fuel shortages[9]. Bingu Wa Mutharika faced criticism in his second term on the basis of violation of human rights (including his stance against homosexuality) and refusal to devalue the local currency (Kwacha)[10]. This led to the freezing of donor funds and, hence, fuel shortages. In no time, Mutharika’s successor upon his death, Joyce Banda, devalued the Kwacha by almost 50% from K166 per $1 to K250. As expected, donor funding resumed, and the crisis eased. Banda only ruled for two years and lost to Bingu’s brother, Peter Wa Mutharika, in 2014. The Peter Wa Mutharika era saw a stable fuel supply.

The current crisis

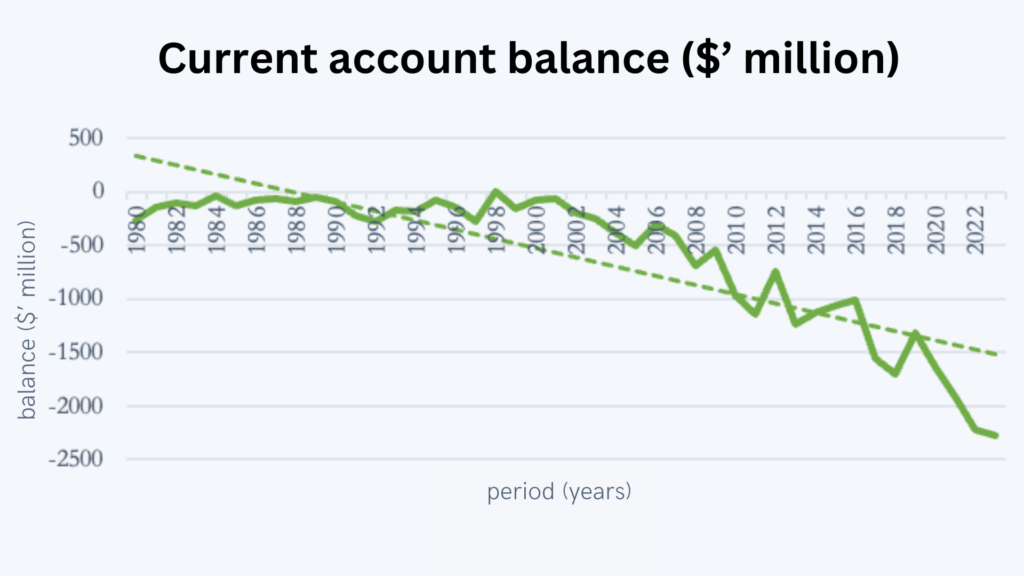

The current crisis has nothing to do with the Mozambican war or donors freezing funds due to conflict with the Chakwera leadership. This is purely a sign of an unattended structural economic issue of an imbalance of exports and imports[11]. Numbers do not lie. Malawi has predominantly been an importing country and has consistently faced trade deficits. Figure 1 below shows the current account balance for Malawi over time.

Figure 1: Author’s illustration of the Current Account Balance for Malawi using data from UNCTAD[12]

As seen in Figure 1, the current account balance has been deteriorating over time. Malawi has been exporting less and importing more. Due to competing imports, including medicines, fertilizers, consumables, electronics, machinery, etc., Malawi has found herself with very little space to import adequate fuel. According to the Reserve Bank of Malawi data, the country spends approximately US$600 million[13] on fuel alone against US$504 million unprecedented earnings from a major export, tobacco, in 2024. Clearly, there is a huge mismatch between the export and import needs of Malawi.

Who is to blame?

It is very easy to blame the current regime for the crisis, but this is a tragedy that has been looming and will likely continue to strike if not addressed. On one hand, the country has not produced enough to export and meet its import needs. Basic economics will tell us that output and aggregate supply are closely related. Basics economics will also highlight the role that private agents play in the production of goods and services, which, when aggregated, form part of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Vividly, private agents (individuals, firms, etc.) have not been producing enough surpluses for export. In any case, the annual productions have barely met domestic demand. There has also not been significant diversification in exports. Tobacco remains the major export for the country amidst anti-smoking campaigns[14]. As it stands, the country will continue to face current account deficits and, no doubt, persistent fuel shortages, and we have no one but ourselves to blame for not contributing to increased and diversified exports.

On the other hand, the government equally shares the blame. Change in an economy largely depends on government policy and signals. Not much has been done to stimulate production and exports in Malawi. If anything, the majority of the regimes have depended on donors and development partners to stabilize the current account. This has just provided cosmetic and temporary solutions to the structural issues that the country has. Nothing but increased exports will solve Malawian fuel shortages. In a developmental state, as claimed in Malawi 2063[15], there should be more government actions and interventions in the economy. The government should lead the way and provide the necessary tools for growth. This is beyond developing policies, programs, and projects and shelving them to gather dust. This is the government coordinating production, supporting private firms, investing in production, and leading the export development strategy. This is coordinated fiscal and monetary policy implementation for increased exports. Unfortunately, very little close to this ideal developmental state has been witnessed in Malawi. Projects deemed as potential game changers like the mega farms and Greenbelt initiative have slowly been rolled out. The provisions of key policies like the National Agriculture Policy (NAP) and National Export Strategy (NES) have barely been implemented on the ground.

What about the current proposed solutions?

To solve the fuel crisis, once again, the government has resorted to cosmetics, the government-to-government (G2G) arrangement. Through this arrangement, the government will be able to import fuel and pay back when it has enough forex to do so (within a maximum window of 180 days)[16]. While the G2G has the potential to ease the current pressure, it does not solve the looming tragedy, nor does it solve the underlying cause of fuel shortages – lack of a diversified economy and having a higher value of exports as opposed to imports. Even if the measure can ease pressure on fuel, what about the other essential imports like medicines? What is clear from all this is that Malawi as a country should address the structural trade imbalance.

CONCLUSION AND WHAT’S NEXT IN 2025

The year 2025 stands as a pivotal moment in the nation’s democratic journey as it approaches the electoral crossroads. Despite the current administration’s economic interventions, significant challenges persist that continue to affect citizens’ daily lives. The upcoming elections will serve as a critical referendum on the Malawi Congress Party’s tenure, with voters having to weigh the party’s performance against its initial election campaign pledges. The fundamental question remains: Has the MCP delivered on its promises to the Malawian people? Malawi Citizens Watch remains committed to its role as an independent observer, meticulously documenting governmental actions and preparing a comprehensive evaluation that will objectively assess the MCP’s five-year governance record. This forthcoming report aims to empower citizens with the factual basis needed to make informed electoral decisions that will shape the nation’s future trajectory.

To continue to track the performance of the Malawi government right up until the next elections in September 2025, go to: https://www.africancitizenswatch.org/malawi

Footnotes

- [1] Read the MCP manifesto here at MCP-Manifesto.pdf

- [2] Detailed tracking of the promises and verified action taken on them can be found at AfricanCitizensWatch | Country

- [3] The Tonse Alliance is/was a coalition of 9 parties which was formed specifically for the fresh presidential elections upon overturning of the 2019 elections results by the court due to irregularities. Read more and some developments at Fall and fall of Tonse Alliance – Nation Online

- [4] Neef launches farm inputs loans in Dowa-Ntchisi | Malawi 24 | Latest News from Malawi

- [5] 2024 Inflation averages 32.2% – MCCCI

- [6] Malawi’s trade imbalance persists, World Bank says – The Times Group

- [7] Joey Power discusses Hastings Kamuzu Banda at Banda, Hastings Kamuzu | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History

- [8] Additional discussion is provided by David Robnson at RENAMO, Malawi and the Struggle to Succeed Banda: Assessing Theories of Malawian Intervention in the Mozambican Civil War

- [9] Diana Cammack Malawi’s poor performance between 1980 and 2002 at Poorly Performing Countries: Malawi, 1980-2002

- [10] Diana Cammack gives a detailed discussion of Malawi in crisis, 2011–12

- [11] Malawi’s trade imbalance persists, World Bank says – The Times Group

- [12] UNCTADstat Data Centre

- [13] Fuel open tender deals to end December – Nation Online

- [14] Tobacco continues to dominate exports – Nation Online

- [15] MW2063 VISION FINAL

- [16] Inside new fuel plan – Nation Online