But when we consider the high rate of informality in Africa, does this mean we should re-think our objectives for financial inclusion, or should we change our focus when it comes to making informal MSMEs compliant?

How far have we come with financial inclusion?

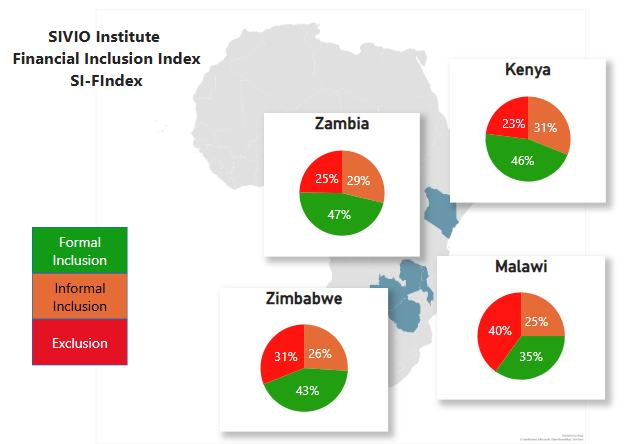

In the last few years, financial inclusion has become an important indicator for economic development in African economies. As of 2018 at least 20 African countries had developed and implemented national financial inclusion strategies with at least 3 more having concrete plans to implement similar policies. A common thread across most financial inclusion strategies is the observed need to focus on youth, women and micro, small and medium enterprises [also known as MSMEs]. In a recent study conducted by SIVIO Institute which involves the development of a Financial Inclusion Index (SI-FIndex) to measure the level of financial inclusion in key African economies (Kenya Malawi and Zambia) we determined that Kenya has the highest level of financial inclusion at 39% followed by Zambia at 34% whilst Malawi exhibiting the lowest levels of financial inclusion at 25%.

Source: SI FIndex Report, 2024

How does compliance link to inclusion?

What is important to note is that countries with high levels of compliance also exhibit high levels of inclusion. Compliance levels in Kenya stand at 59% and compliance levels in Zambia are at 58%. This means those groups have registered their businesses with local authorities or Registrar of Deeds and have made some efforts to become tax compliant. Formality gives these enterprises access to financial products and services from banks, microfinance institutions and some neo-banking institutions that require identification through a government authority.

In the development of this index, we discovered that for many countries, inclusion is a measure of access to formal financial products and services which are regulated by governments as noted by the definitions put forward by the countries we studied. However, there is a whole ecosystem of enterprises that are not registered and therefore do not have access to these products and services. In Africa, this informal cohort of start-ups can make up to 50 to 60% of the population of enterprises in the economy. These groups range in size but will generally fall into the micro or small category with less than six (6) employees.

The most significant reasons why these informal MSMEs choose to remain non-compliant range from complexity of the taxation system, bureaucracy, the expenses associated with compliance through payment of taxes and the lack of information surrounding the requirements needed for one to become compliant.

Who Are the MSMEs?

A lot of these micro and small businesses are the sole trader operations that we see on our roadsides working as vendors from whom we buy a variety of products from clothes to street food. This group despite being informal, is important for our economies. They contribute as much as 60% to employment. So when dealing with this important group by virtue of their contribution, it is important to start to consider if the strategies for financial inclusion we have promoted to date (which are largely top down) are likely to make significant progress considering they may not necessarily meet the needs of these informal groups of enterprises.

How can we change the compliance narrative?

Although formal inclusion is high in Kenya and Zambia, informal inclusion is also high with about 30% of micro small and medium enterprises using informal channels to access financial products and services. This means there is a whole community of MSMEs and a whole community of service providers that continue to operate away from the government’s regulation. We can see this as a threat to the fiscus or the opportunities for a different type of engagement focused on the strength of the community. In a recent piece by Tendai Murisa called “The Big Bet”, he emphasizes that communities and the work that they do between and amongst each other is the strength that societies need to maintain their fabric of existence and survival. Adopting this narrative, one can start to consider new ways to engage with MSMEs leveraging on the strength of the community rather than the ability or resolve of the individual to become compliant.

Betting on communities as a way of fostering compliance.

What if we reconsidered our efforts in financial inclusion to focus primarily on growing the community engagement of small businesses in their places of informality giving them the support, they need to raise funds informally and even become compliant through these small community spaces? Historically it has always been easier to mobilize communities through peer-to-peer engagement rather than a top-down approach. We have seen this in community projects of various kinds. So instead of trying to push a top-down approach where the government continues to demand accountability, is compliance not easier to encourage from a community level within the context of small investment groups, centres of information access and centres of mutual support to build and strengthen the business unit?

It is important, however, to consider the concerns of MSMEs raised countless times as reasons for non-compliance. For example, affordability and the complex nature of the systems involved. Considering the important role that MSMEs play it would be better to have much lower tax bans for micro and small enterprises (anything above 10% would probably be considered too much). This is not because MSMEs are asking for a handout, on the contrary, we need to understand the responsibilities many of these start-up founders have on their shoulders. Many of the micro-enterprises are female and vendors. Whether they are single, married or divorced, what is important is their bread-winner status in a society that was previously difficult for them to break through.

Compliance as a tool for continued restriction?

For these women, the complex and cumbersome compliance requirements are just another hurdle placed by a system that may come across as oppressive rather than supportive. For the many young people who are running businesses on the continent their choice to engage in entrepreneurship is usually prompted by the lack of formal employment opportunities available around them. Their engagement in productive entrepreneurship means less time for negative contributions to society which can take many forms including addiction to social media, crime, drug use, and plain idleness.

It would be more beneficial for the fiscus to include them at lower tax rates, and then increase these tax rates as their businesses grow (to medium status), understanding that micro and small businesses already have many inherent and environmental challenges to overcome. Read more about the SIVIO Institute financial inclusion index (SI-FIndex) and find out more about Tendai Murisa’s Big Bet on engaged communities here